As a teacher trainer this is a question that preoccupies me on a daily basis. Moreover I am not alone in this enquiry, indeed a major area of research has been to examine the impact of training on a teacher’s development. Researching the development of a teacher as a result of a training course is a challenging task. Conclusions of these studies vary from training being highly significant to almost negligible in terms of a teacher’s professional development. These discrepancies highlight the fact that measuring the impact of training is complex. The initial problem is defining ‘development’. Most studies resolve this difficulty by equating development with ‘change’. The logic proceeds along the lines that if the aim is to promote development then by definition there needs to be change. This change can be identified and potentially even measured. Studies can focus on changes in classroom behaviour (by observation), or in knowledge (tests) or, currently popular, changes in teachers’ beliefs (by questionnaire or verbal or written report).

Such studies have a number of limitations. Firstly, failure to take a longitudinal perspective of a teacher’s life and assume that change can be identified at a specific stage (for example, after a training programme). Secondly, reliance on one method of data collection and failure to triangulate information. This is a flaw as experienced teacher trainers will concur that what a teacher professes to do in an oral or written report is not always what they demonstrate when observed in the classroom and vice versa. The real question needs to reveal the nature of teacher development. Are we examining change in terms of what a teacher does, knows or believes? Until we define the nature of teacher development then the change processes may remain too deeply hidden even for the most conscientious researcher to uncover.

Journeys in Teacher Education

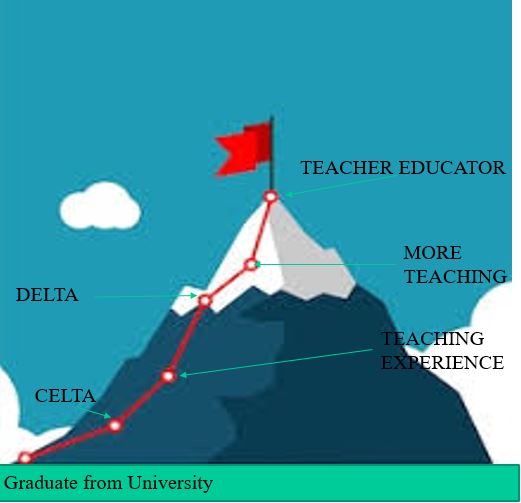

Describing a teachers’ development as a journey is a well trodden metaphor (Godfrey, 2011). The allegory is apt however since a central concept of a teachers’ professional development implies change, moving from one position to another as in a journey.

As a journey has a destination and a route so does teacher development. The destination is knowledge, the route is the experience we need to obtain the knowledge. Teacher development is a life long journey and a commitment to development and change.

In my experience many teachers when they set out on this journey innocently perceive it as a well trodden path with the route clearly signposted and the staging posts marked. However this is rarely the case and it is often only by getting lost and having to cope with chaos that we really learn from experience. We learn more about the jungle by hacking through it on foot than reading about it in a book.

The Landscape

Before we can embark on our journey of teacher development, we need to consider what kind of journey are we on. What kind of landscape are we travelling through? How are we travelling? When considering the nature of teaching: Is teaching best described as a job (performing routine and repetitive tasks)? A career (life-long involvement and developing expertise with experience)? A profession (social responsibility and professional identity)? Or perhaps a vocation (personal significance and autonomy)? For most experienced teachers their perspective of their role may engage all of these characterisations. How teachers view their role and indeed how society at large views the role of a teacher is influenced by perceptions of the nature of knowledge (epistemology) and how knowledge is conveyed to learners.

So we can view a teacher’s role from a variety of perspectives and these ‘levels of perception’ are important when researching the nature of a teacher and teacher learning. This distinction is rarely acknowledged as most research studies on teacher learning are locked into an epistemological stance that sees teaching from one perspective only. Teachers’ roles are categorised into concepts of teachers as technicians, reflective practitioners or transformative intellectuals. These are not mutually exclusive categories but represent a cline as teaching involves elements of routine task and behaviours at one end, to reflective thinking and effecting personal and social change at the other.

The Route

These levels of perception are mirrored historically in English language teaching where there has been an evolution from behaviorism and a focus on techniques, practices and methods through to learner centered approaches concerned more with the learner and affective factors. These changes in perception are influenced by psychology and second language acquisition research. They alter our perceptions of the landscape and the route we need to take on our teacher’s developmental journey. .

Empiricists vs Rationalists

There is a vast quantity of literature describing a teacher’s professional development but also little consensus and considerable confusion. This confusion appears to be largely caused by the shifting epistemological perspectives in which the focus of enquiry has targeted different features of teacher learning. Prior to 1975 the dominant research paradigm concerned the relationship between the teachers’ classroom behaviour, students’ classroom behaviour, and student achievement. This research model, advocated by Empiricists, focuses on teacher behaviour and observable outcomes of empirical observation. This was followed by a Rationalist domain of enquiry known as ‘teacher cognition’ studying what teachers know and think. This vast volume of research data enables applied linguists to boldly claim that now they have an understanding of how teachers conceive of what they do: what they know about language teaching, how they think about their classroom practice, and how that knowledge and those thinking processes are learned through teacher development and informal experience on the job.

This confident assertion can only be offered from a convergent oriented research paradigm that perceives the journey of teacher development as consisting of one route and one destination. There is an underlying reductionist assumption that there are static generalisations and truths to be uncovered from the research data. I argue that we also need to consider a third possibility of a more dynamic, divergent approach to teacher learning and development that views individual teacher’s behaviour and thoughts as being influenced by a set of ‘beliefs’ that are personal, dynamic and often subconscious and these internalized perceptions, beliefs and feelings relate to who one is in the world. In other words we need to accept that there may be many routes and destinations on the teacher development journey.

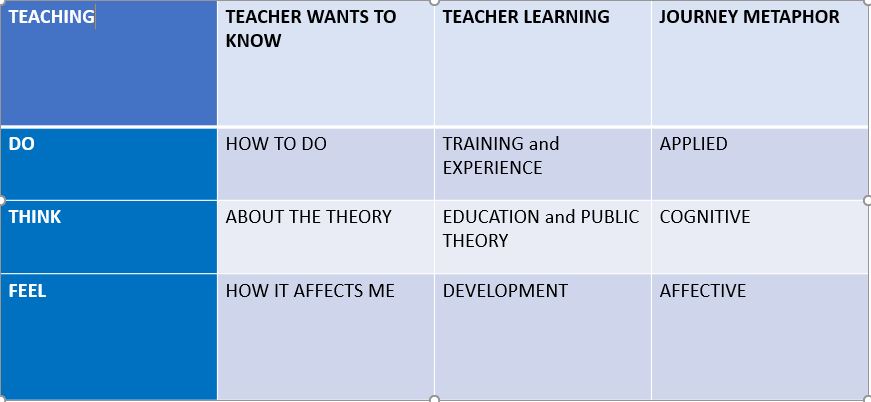

All three paradigms, focusing alternately on what teachers do, think and feel are all components of the developmental journey. They represent three ‘learning journeys’ that although they can operate separately, they are inextricably linked.

The Destination

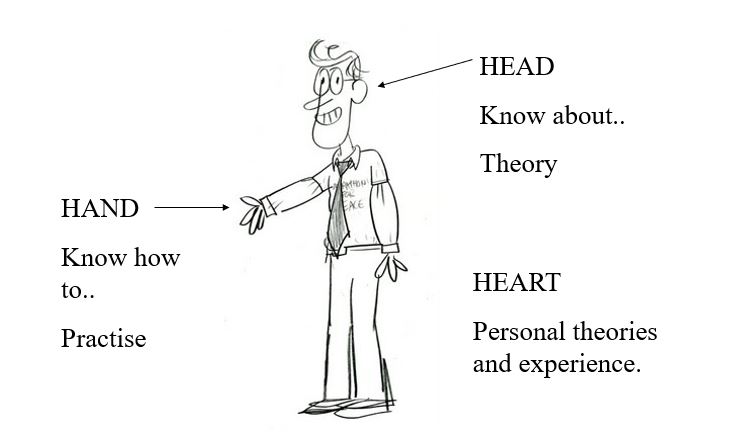

The question we need to address is: what is the destination? What knowledge does a teacher need? Malderez and Bodoczky (1999) identify three levels for describing a teacher’s knowledge. They depict the relationship visually using the metaphor of an iceberg.

Above the water level of the iceberg there are the observable behaviours of what happens in the classroom. There are a number of approaches in the literature focussing on investigating teachers’ practical classroom knowledge. One approach takes teachers knowledge as personal, practical and tacit knowledge developed in the course of engaging in the act of teaching and responding to the context of the situation. However this knowledge is not always easily accessible to the conscious mind as ‘we know more than we can tell’ (Polyani, 1967). Teachers with experience act in the cassroom in a certain way but can be hard pushed to explain why they responded in certain ways. There is a distinction between a teacher’s tacit knowledge and formalised knowledge that can be disseminated. Schon (1983) proposed that what teachers do in the classroom can be defined as ‘knowing in action’, that is, practice reveals a knowing that does not stem from intellectual operation. In other words knowing how to teach does not depend on formalised knowledge (as medicine and law). Expert mathematicians may not be the best mathematics teachers and effective language teachers may not have much knowledge of linguistics. Hence the distinction between what teachers do in the classroom (practice) and what they know (theory) has generated contrasting opinions. Are the actions of an effective teacher more attuned to the arts, where there is valuing of the individual, the particular, the local, the intuitive, the imaginative: or to science, where there is valuing of the general, the systematic, the objective, the publicly shared?

In the 1980s cognitive learning theories shifted research to questions under the water level of the iceberg to examine what teachers know, how they use this knowledge and what impact their decisions have on practice. Deeper under the surface are beliefs. Beliefs, it is claimed, greatly influence teaching, are unconscious, deep rooted and hard to change. Even deeper into the depths of the iceberg we have teachers’ feelings and attitudes to teaching. Attitude is a way of thinking that inclines one to feel and behave in certain ways. It is influenced by factors such as status, level of pay, political structure of the school and other social forces. Positive and negative attitudes to teaching will change, as indeed the social context in which the teachers operate and find meanings will change.

In order to conceptualise a teacher’s development as a metaphorical journey, we need to frame the journey into three ‘learning worlds’.

1. The Applied World: Classroom teaching (procedure and techniques) and the teacher’s visible behaviours are the physical manifestations on the journey.

2. The Cognitive World: Teaching design and knowledge and the teacher’s mental ideas and concepts are the route. The symbolic journey is cognitive and non observable.

3. The Spiritual World: The final element is the teacher’s inner responses (how they make sense of the journey in terms of individual feelings, beliefs, attitudes and values. The changes in the traveller’s feelings, moods, thoughts and attitudes to the journey are not identifiable to the external observer but nevertheless these are the changes that determines the traveller’s sense of self, her identity and in terms of the traveller’s development, the changes that should interest us the most.

Typically research into a teacher’s developmental journey has focussed on specific features of the journey, predominantly either focusing on the applied world and the observable phenomena or the symbolic journey and the learning processes or the real or imagined impressions of the teacher as they go on their journey. however, in reality all these world are interacting and interlocking – all essential features of the same journey.

The role of the trainer.

What is the role of training in the developmental journey?

If teaching is at its roots the acquisition of pedagogic skills and these skills are acquired primarily through classroom experience , then what role, we can ask, does a training course have on a teachers’ development?

Focus on techniques: Is training about providing a recipe of skills?

One answer is to view a training course as a transmission process where the trainer demonstrates a recipe of techniques for trainee teachers to practise. The analogy is the guide in the jungle demonstrating techniques for climbing a rock face, building a shelter, navigating by the stars. Indeed, this logic is applied to more rigid teaching approaches (i.e. Audiolingualism) that attempt to make teaching (and learning) languages (and by extension teacher training) formulaic and ‘teacher proof’. This conception of training only makes sense if the teaching context is stable. However no learners or groups of learners respond in an uniform manner. Teaching, as a social practice, is constituted through communication and coordinated action: it depends on the often unpredictable ways in which learners act and respond to the actions of others. One could argue of course that one method of reducing the unpredictability of teaching is to restrict the number of possible actions and activities in classrooms. McDonald’s fast food chains provide a parallel analogy. The limited number of items on the menu and the global uniformity of both the preparation of the food and the layout and working procedures of the staff restrict the number of different activities available to staff and customers. This makes the experience of ordering a ‘Big Mac’ the same all over the world irrespective of local language and cuisine. We can envisage a ‘Big Mac’ manual to ELT teaching. Many classroom actions are habitual in nature, the patterns of action can be acquired in training and practised until highly proficient through experience.

What happens though when the tried and trusted techniques fail? Pedagogy is more than the relationship between action and consequences. This is particularly self-evident in teaching when the same lesson taught to different groups invariably has a variety of outcomes (a world apart from the standardised Big Mac). There is an intersubjectivity between the worlds of action, mind and self. When the lesson starts going pear shaped, we need to call on the world of reflective skills and critical thinking.

Focus on theory: Is training a form of brainwashing?

Undoubtedly, while teachers need training to be grounded in classroom practice they also need the theoretical rationale. Why does this work? How should theory be conveyed in a training context? The desired outcome of the course is greater shared tacit knowledge. Many teachers demand a deductive approach (as do many learners): “Tell me what I need to know”. However a lecturing approach to theory rarely is effective as abstract ideas and processes mean little to participants without the reference point of personal experience. Indeed this theoretical indoctrination without opportunities for critical reflection or practical application is not dissimilar to a form of brainwashing.

On the other hand it is also possible to criticise more inductive approaches to training too. Constructivist theory suggests that shared tacit knowledge will be the outcome where teachers participate in activities and decision-making, have a sense of responsibility and engage in collaborative work. However most teachers would be wary of putting learners into a group with the expectation that through interaction and dialogue alone effective learning would be achieved. There are numerous mitigating factors concerning individual’s professional identity and pervasive influence of the context. A balance of guidance and discovery is required by the trainer depending on a range of factors such as depth of teaching experience and factors related to personality and self esteem.

In order for effective interaction and collaboration to exist there needs to be a culture of trust and mutual respect. Opportunities for interaction may be less significant in terms of learning and meaning construction and more important for establishing and exploring personal identity and a ‘sense of self’. There is a danger of creating superficial and contrived forms of interaction or ‘sharing for the sake of sharing’. What is needed, in other words, is a model of teacher education that acknowledges the non-causal nature of training interaction and accepts the value of personal enhancement as well as technical processes. How teachers’ feel about themselves enhances their technical, reflective and critical skills. Greater confidence means better teachers.

I can illustrate what I mean about the non-causal nature of training with an analogy. When a chef enters the kitchen to cook a meal, he can predict the outcome of the process with confidence. He prepares and mixes the ingredients, places them in the cooker and most days the outcome is similar: a trainer enters the training room with a group of teachers and can not predict the outcomes of the process in the same manner. Each group of participants will behave differently. This requires an inner security and confidence in order to appreciate that there may be a loss of clarity and control but not a loss of one’s personal identity.

We can conclude by stating that there are at least three learning journeys. The physical journey seeks to answer ‘how’ questions and involves physical action and classroom procedure. The reflective journey seeks to answer ‘what’ questions and takes us out of ourselves to consider abstractions, metaphor and generalisations. We travel this road to create meaning in a rationale objective manner. The spiritual journey seeks to answer ‘why’ questions and takes us into our inner selves to consider who we are, our spirituality, desires, identity. We travel this road to discover our subjective inner truth.

Creating our own reality.

Of course the metaphor of learning as a journey is a simplification. A teacher’s developmental journey cannot be concretized into a definable product or process: knowledge and learning are inseparable and not bound in time and space. Knowledge can enter our consciousness with blinding clarity one moment and then dissipate into wispy clouds the next. We have the ability to re-imagine, re-create and re-invent past experiences and fashion them to our desire, highlighting episodes that reverberate with our inner sense of self. Equally we create our future journeys through imagination and visualisation. We dream and fantasize. We create our learning journeys and fashion the landscape in our own reflection. We become the teacher we are through the way we engage with what we learn.

The challenge for teacher education, then, is firstly to make teachers aware of the landscape and the journeys they create for themselves and help them understand how they created their landscape and especially why. The answers to these questions lies in an exploration not only of what teachers do and think but also an exploration of who the teacher is, in other words their sense of self.

Biibliography

Godfrey, J. T. (2011) Journeys in Teacher Training and Education. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

Malderez, A. and Bodoczky, C. (1999) Mentor Courses: a resource book for teacher trainers. Cambridge University Press.

Polyani, M. (1967) The Tacit Dimension. New York. Doubleday.

Schon, D. A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. London: Temple Smith

What a great article. I have always believed that great teachers know ‘why’ they do different activities in the classroom, and now I realize how that lies in deeper levels of their character, i.e. their inner responses towards classroom incidents. Also, I really enjoyed how confidence has different interpretations in ELT compared to other areas in our lives. Sometimes it is not about a fixed outcome, but about realizing and acknowledging the possible outcomes so that they should be coped with. I kind of knew it in some ways, but now I am ‘aware’ of it. However, I don’t think limiting the range of activities in a classroom would be beneficial just like a Macdonald’s policy as this was the actual reason that the ELT community moved on from methods into post-methods era.

Thanks Tom

This was a very informative article about the nature of training and teacher education. The three key words of ‘do, think and feel’ demonstrate the significant role of the teachers, not only based on the knowledge they possess but also their perception of teaching and, more importantly, they way they feel. In fact, it is a teacher’s attitude and and thought that could influence the knowledge they acquire and, consequently, the way they behave in the classroom.

The role of the trainer and training programs, I understand, is enabling teachers to embrace all these necessary elements and make use of them as a package.

Thanks, Dr. Godfrey

This is insightful. I never thought about the difference between training and development, let alone education. For me, they were always related to each other and interconnected. They still are, but reading about them here gives me a clearer picture of “what do I want to be?” It’s not about which one is better, of course, but it is about which one is closer to my heart.

Thanks for sharing, Tom!

Reblogged this on thoughts-for-teaching.

Thank you for your great article. As you mention ,teachers’ feelings enhance their technical , reflective and critical skills. I also agree that confidence means better teachers. Making teachers aware of the landscape , the journeys , who they are and what they want help them perceive the trainings and classrooms better .

Teacher development is an ongoing and dynamic process that requires a commitment to lifelong learning and a dedication to enhancing the educational experience for students. By continually improving their skills and staying up-to-date with educational advancements, teachers can have a positive impact on their students’ learning outcomes.

Thank you Tom for your great work

I really loved the analogies drawn here. It`s easy to predict the outcome when you are a chef or work in a McDonald`s but for teachers/trainers the outcomes depend on a variety of factors, and perhaps this grately contibutes to our development. Also, I highly resonate with “we know more than we can tell” since very often it`s really hard to express or explain something you know in class. It makes me doubt whether I am not good enough to be a teacher or it`s something temporary. Therefore being confident as an educator is vital and just necessary to deliver a good lesson or a training session, This also highlights the importance of our feelings and beliefs.

Thanks for the article. As you put forward, looking at a teachers development from one single perspective is not possible. So, in my training session, I will focus on how to impact on teachers’ beliefs and attitudes first.

Your article points to important issues about trying to measure the effect of training on teacher development – or “change”. I guess change is expected as a result of a training course because of the definition of teaching or learning – When we teach, we expect change in behavior. Even if we expected teachers to do that, if would be more valuable to see how the change occurs and what happens in time – in my opinion. What happens when they teach very low levels? What happens in five years? What happens to their teaching practice when their family life changes, for instance? That kind of study would be very difficult but worth the while to see the real impact of any training on any teacher.

Defne A Midas

Thank you for this enlightening article. It is really exciting to percieve teaching as a non-ending journey. I highly agree with your point that confidence makes better teachers along the way, and this confidence is the outcome of our developmental journey as teachers. I always believe that as we teach, we also learn a lot not only about teaching but also ourselves as an individual. So, it seems to me that being a teacher is a transforming identity that always lives within us in each area of our lives.

Your article beautifully highlights how training shapes teachers over time, beyond just the classroom. Confidence grows with experience, and so does our understanding of both teaching and ourselves. It’s inspiring to see teaching as an evolving identity rather than just a profession. Change is inevitable, but the real magic lies in how it unfolds. Thank you for this thought-provoking piece!

Dear Tom,

This article offers valuable insights into the development and role of trainers in education. It highlights the importance of incorporating reflective and critical thinking skills into our lessons. By applying constructivist and cognitive theories, we can enhance student engagement and improve the effectiveness of our teaching. This journey is essential for uncovering our true identity as educators, empowering us to connect more deeply with our purpose and impact. Thank you for your great effort. It’s a very fruitful text in terms of its content.